I grew up with the idea that scientists crash ideas into walls. My mother is a botanist and an ecologist. My father is an ecologist, meteorologist, and nuclear chemist at the various steps of his career. And while it's true I have always taken what scientist say with a grain of salt, I always assumed that was because there were a few bad-apple scientists.

The reality, as always, is a bit more complicated. Science is nowhere near as rigorous as it likes to make us believe.

Now, a bit of a disclaimer. I am not saying the scientific method doesn't work. The scientific method works by taking hypotheses and putting them into experiments which can prove them wrong. The more likely the experiment will disprove the thesis if it is incorrect, the stronger the experiment. This process of looking for a reason to throw an idea out is called disconfirmation.

Now, the scientific method does have limits. There really aren't that many "scientific" things you can run experiments on or observe directly, but the general rule of disconfirmation leads to solid ideas everywhere.

The problem, though, is that many parts of science operate like a business. The peer review publishers are often concerned with sales of the periodical, and the individual scientists are concerned with their own careers. Let's start with Peer Review:

So we have little evidence on the effectiveness of peer review, but we have considerable evidence on its defects. In addition to being poor at detecting gross defects and almost useless for detecting fraud it is slow, expensive, profligate of academic time, highly subjective, something of a lottery, prone to bias, and easily abused.

SOURCE. If you've read the Global Warming thread you probably recognize this. This is Richard Smith, former editor and chief executive at the British Medical Journal. I really recommend reading his article (or at least glancing through it) because he goes through all these faults of peer review in great depth, along with possible fixes--and why he thinks they won't work, either. This is his bottom line;

So peer review is a flawed process, full of easily identified defects with little evidence that it works. Nevertheless, it is likely to remain central to science and journals because there is no obvious alternative, and scientists and editors have a continuing belief in peer review. How odd that science should be rooted in belief.

That's not what I wanted to hear.

The real problem is that peer review has become a staple of science. Peer review is an expensive process, so these journals have a very high rejection rate; in excess of 90%. This means scientists have an incentive to fudge results to get the editor's attention, and then peer review acts more as a luck stamp--or worse, an "I like you" stamp--which really doesn't mean anything besides membership into scientific canon.

One reason is the competitiveness of science. In the 1950s, when modern academic research took shape after its successes in the second world war, it was still a rarefied pastime. The entire club of scientists numbered a few hundred thousand. As their ranks have swelled, to 6m-7m active researchers on the latest reckoning, scientists have lost their taste for self-policing and quality control. The obligation to “publish or perish” has come to rule over academic life. Competition for jobs is cut-throat. Full professors in America earned on average $135,000 in 2012—more than judges did. Every year six freshly minted PhDs vie for every academic post. Nowadays verification (the replication of other people’s results) does little to advance a researcher’s career. And without verification, dubious findings live on to mislead.

Careerism also encourages exaggeration and the cherry-picking of results. In order to safeguard their exclusivity, the leading journals impose high rejection rates: in excess of 90% of submitted manuscripts. The most striking findings have the greatest chance of making it onto the page. Little wonder that one in three researchers knows of a colleague who has pepped up a paper by, say, excluding inconvenient data from results “based on a gut feeling”. And as more research teams around the world work on a problem, the odds shorten that at least one will fall prey to an honest confusion between the sweet signal of a genuine discovery and a freak of the statistical noise. Such spurious correlations are often recorded in journals eager for startling papers. If they touch on drinking wine, going senile or letting children play video games, they may well command the front pages of newspapers, too.

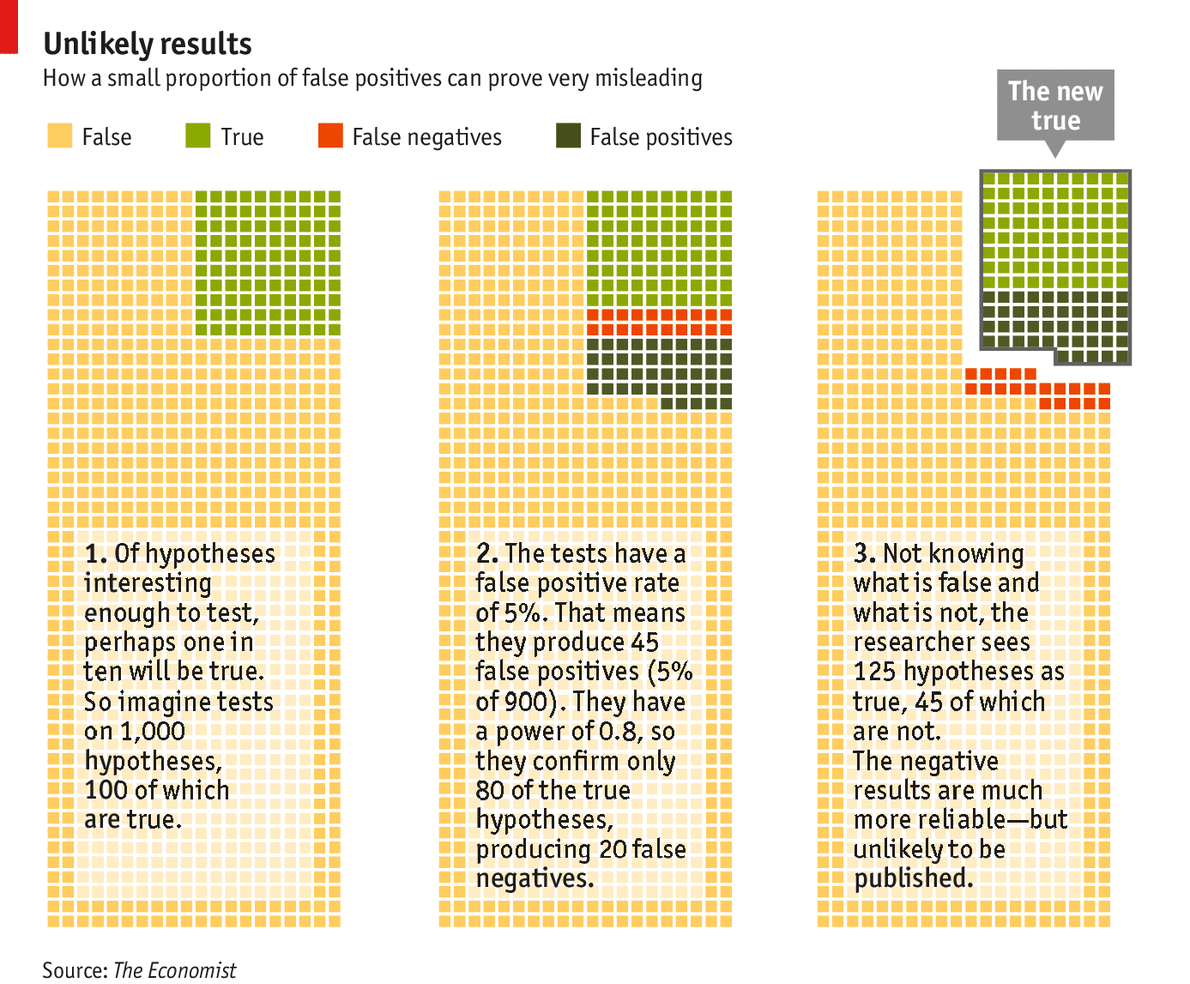

Conversely, failures to prove a hypothesis are rarely even offered for publication, let alone accepted. “Negative results” now account for only 14% of published papers, down from 30% in 1990. Yet knowing what is false is as important to science as knowing what is true. The failure to report failures means that researchers waste money and effort exploring blind alleys already investigated by other scientists.

SOURCE (Emphasis added).

Here is a little infographic from this op-ed to consider:

So we simultaneously have more false positives and LESS verification work than ever. Scientific knowledge is cumulative. Potentially decades of research could be in error.

Works Cited (in order of appearance):

http://jrs.sagepub.c...t/99/4/178.full

http://www.economist...ence-goes-wrong

Edited by Egann, 10 October 2014 - 12:21 PM.